a thousand wounds

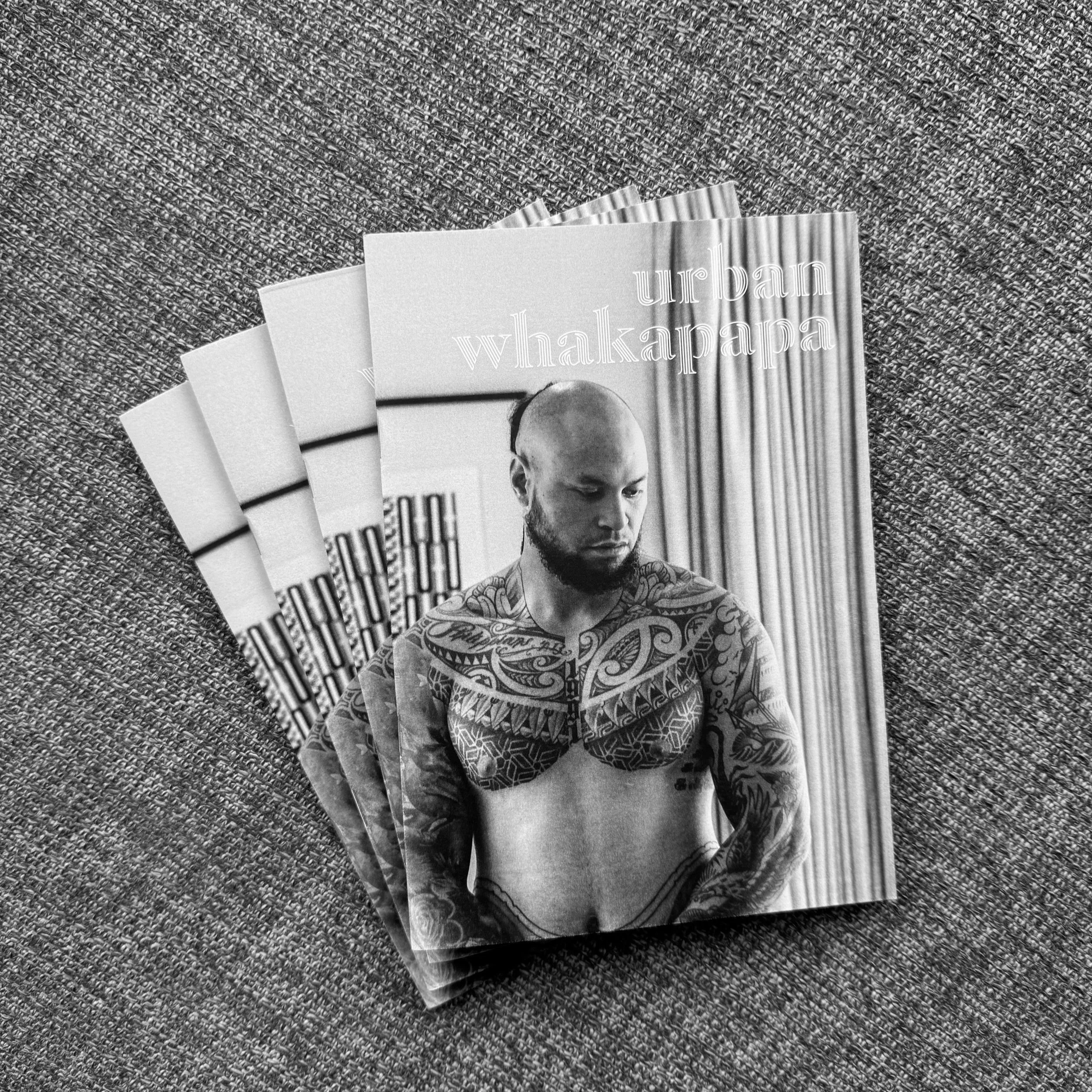

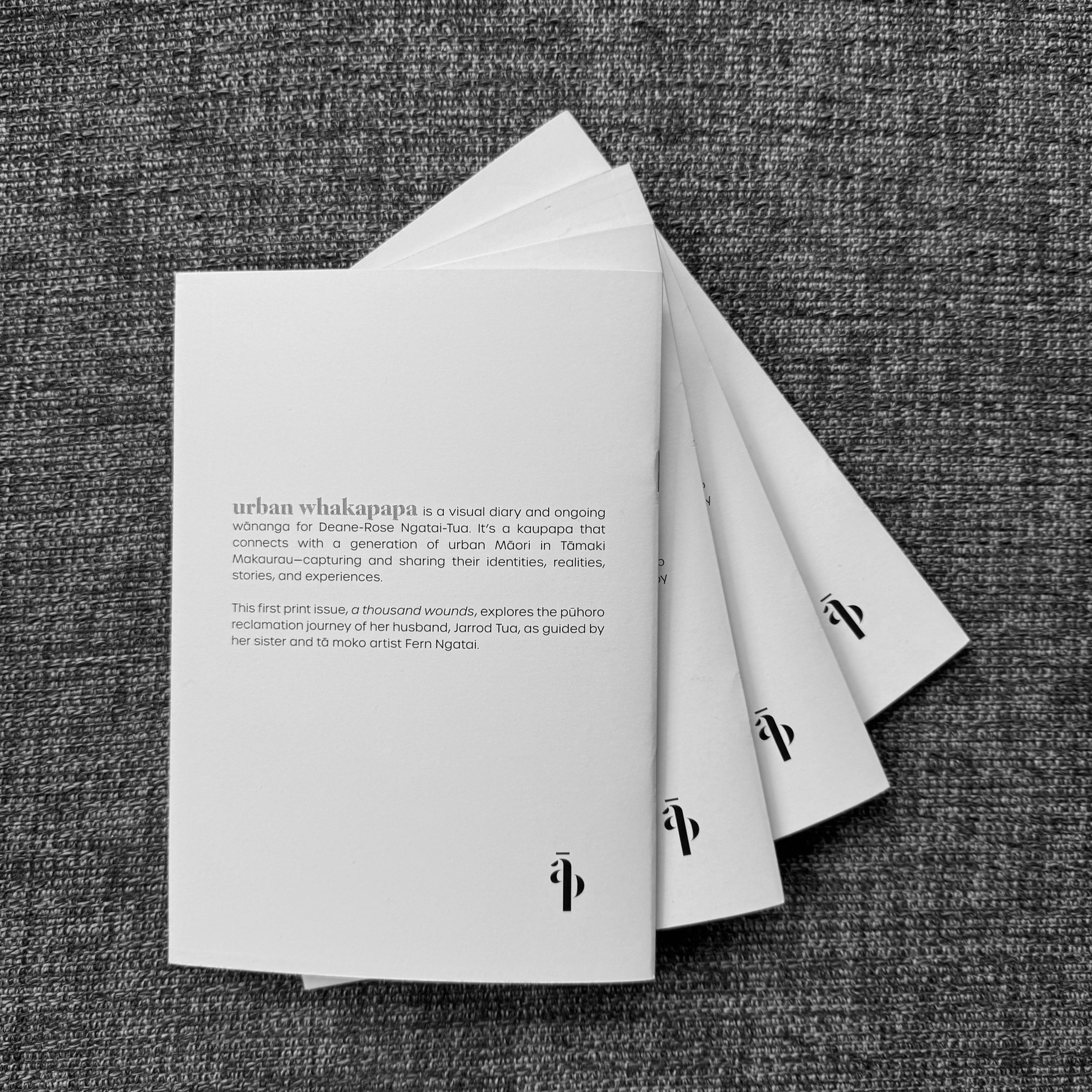

Earlier this year, Āporo Press put out a call for zine submissions, and together we created urban whakapapa: a thousand wounds.

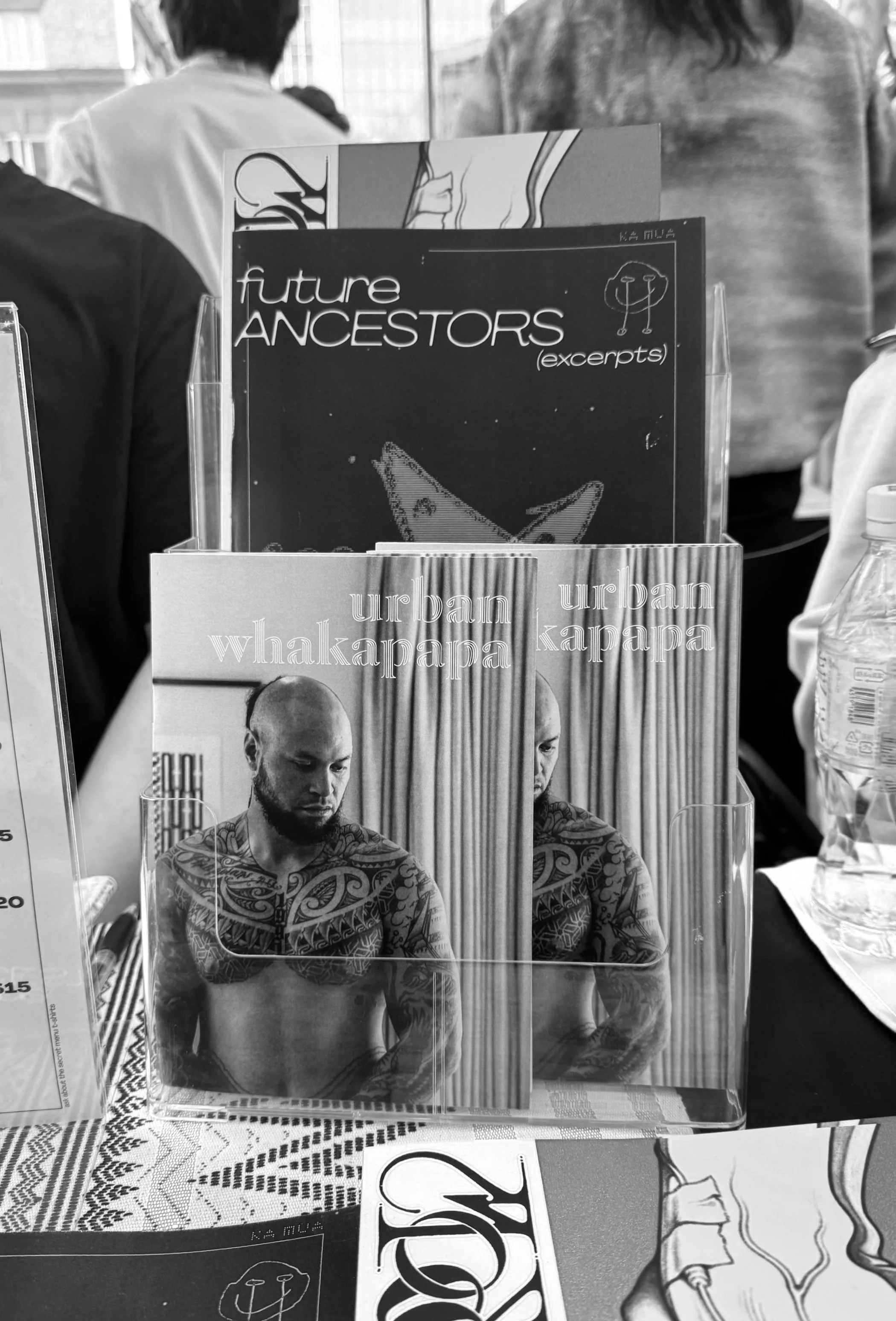

Āporo Press launched urban whakapapa: a thousand wounds at Auckland Zinefest on Sunday 7 July. It's available now through Āporo Press.

The zine shares Jarrod Tua’s pūhoro journey and what it means to reclaim pūhoro in our urban Māori whānau in Tāmaki Makaurau. You can also read Jarrod’s full story here.

Below is the full introduction I wrote for the zine, followed by some photos of the publication and a look inside the pages. I also share some reflections on working with Āporo Press and why the zine format felt like the right fit.

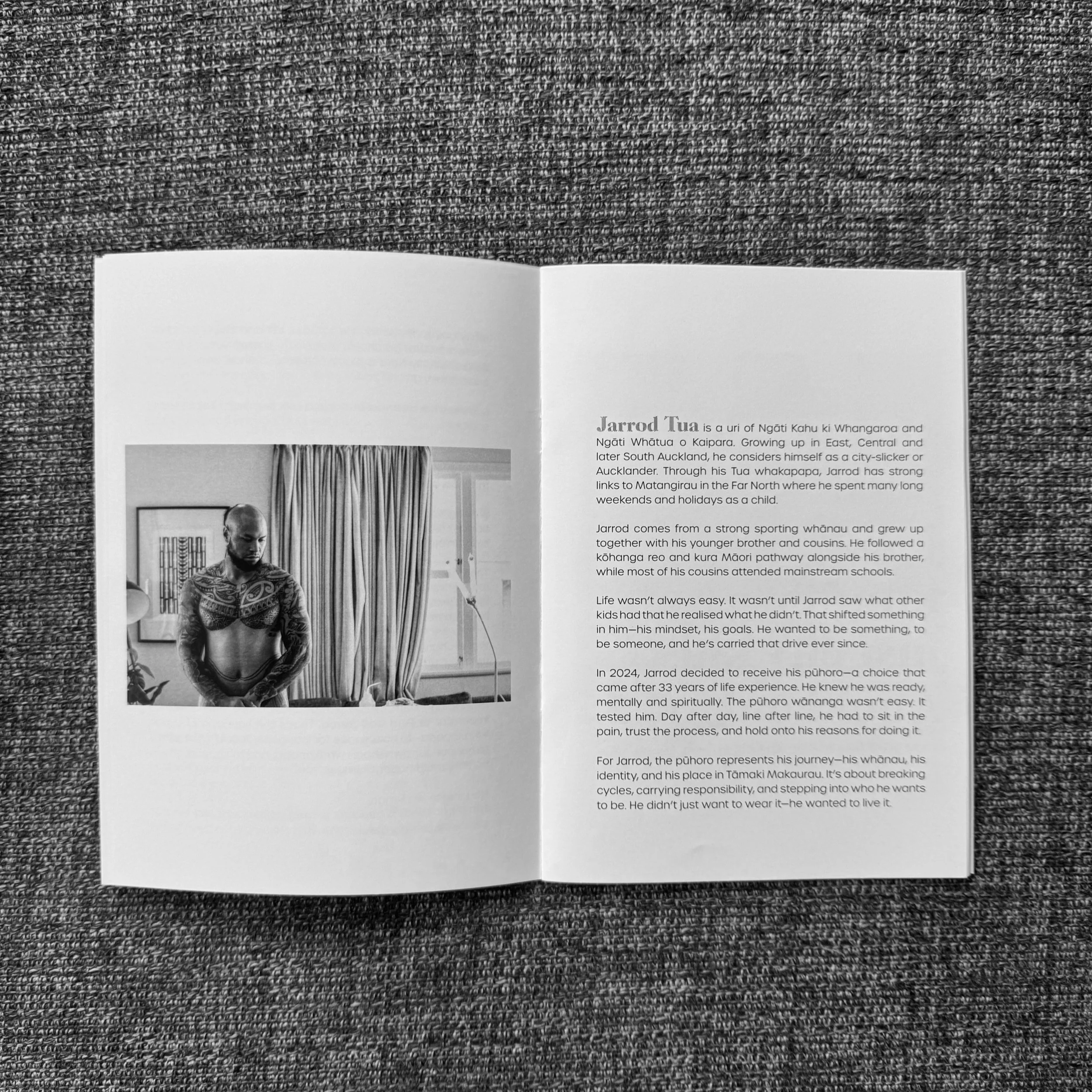

In March 2024, Jarrod Tua undertook a six-day wānanga to receive his pūhoro in our whare in Kelston, Tāmaki Makaurau, by my sister, tā moko artist Fern Ngatai (aka Flows by Rau). A year later, I sat down with Jarrod, my husband, to reflect on the experience, the journey, and everything the pūhoro has come to mean to him. Jarrod’s words—raw and unfiltered—follow here alongside my images.

This kaupapa shares an intimate insight into the reclamation of pūhoro within our whānau. It reflects what reclamation looks and feels like for an urban Māori whānau in Tāmaki Makaurau. It touches on why it matters and its impact on us, our tamariki, and our wider whānau.

Our shared story starts with whakapapa

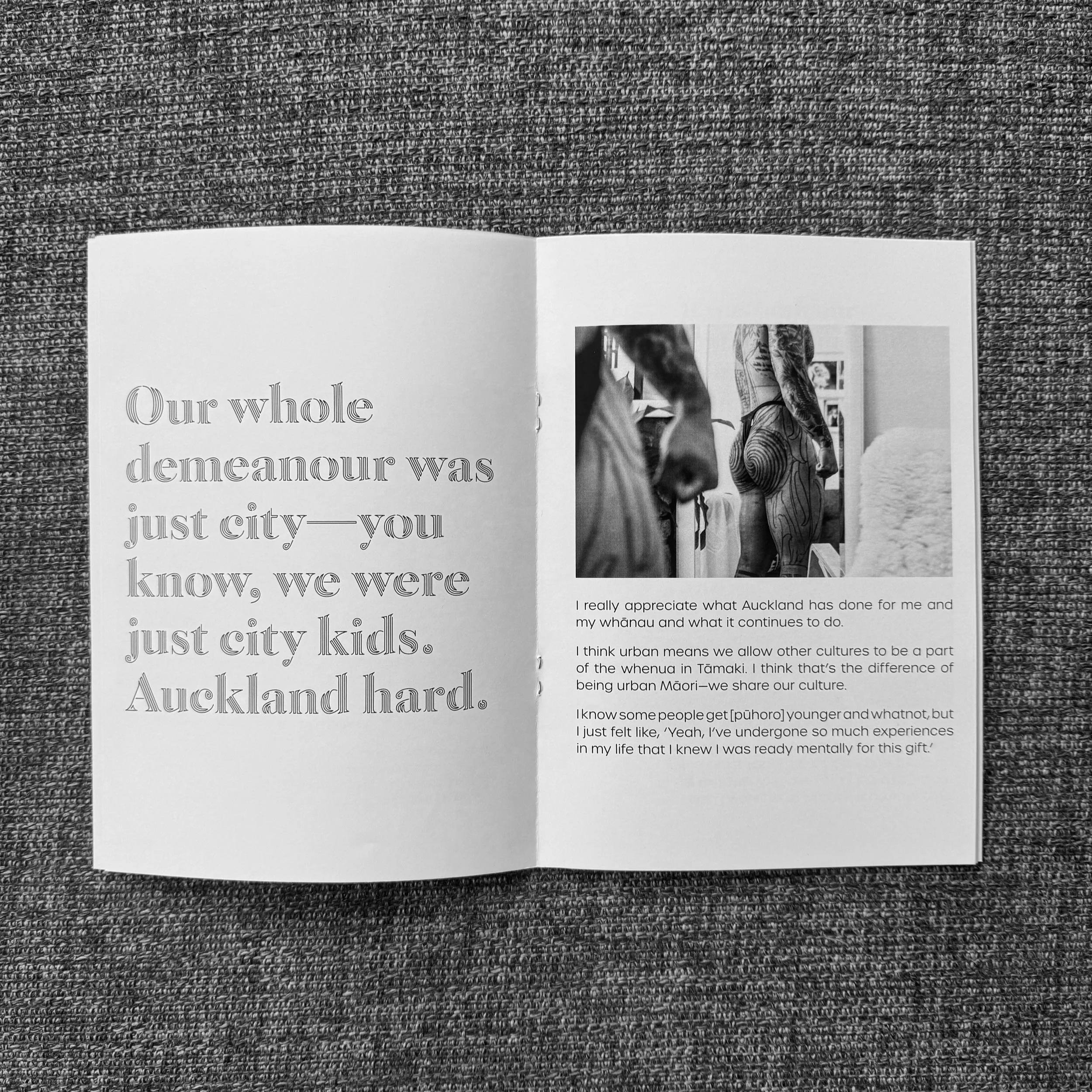

We were born in Tāmaki Makaurau as second-generation urban Māori. We were raised amongst the many cultures and ethnicities of this city—connecting across cultures is a part of our identity. We followed Māori-medium education pathways—navigating te ao Māori and te ao Pākehā. Tāmaki Makaurau is a place of opportunities and possibilities. Growing up as ‘city kids’ is part of our story. These lived experiences have shaped the people we are today.

The term urban Māori helps us to describe this whakapapa, and our identities as tangata whenua born and raised away from our tūrangawaewae, marae and iwi. It helps us to unpack our journeys and identities and process some of the disconnection, shame, and trauma that comes with it.

I also interviewed Fern online for this kaupapa while she was travelling in Europe. As I was relistening to Fern’s interview to help me write this, I was overwhelmed with roimata, and this mamae fell out of me—grieving for what others in our whānau have missed out on. For what so many of our people are still missing out on. And an overwhelming sense of gratitude, for the power that sits in our stories, in our acts of reclamation. Whether that be moko or pūhoro, te reo Māori, kōhanga reo, kura kaupapa.

The kaupapa of Urban Whakapapa is important to me. Holding wānanga with my own whānau to capture and process our journeys of mana motuhake. Reflecting those back on ourselves. Acknowledging the impact those acts have on our lives—and on the generation that follows.

Inside our pūhoro wānanga

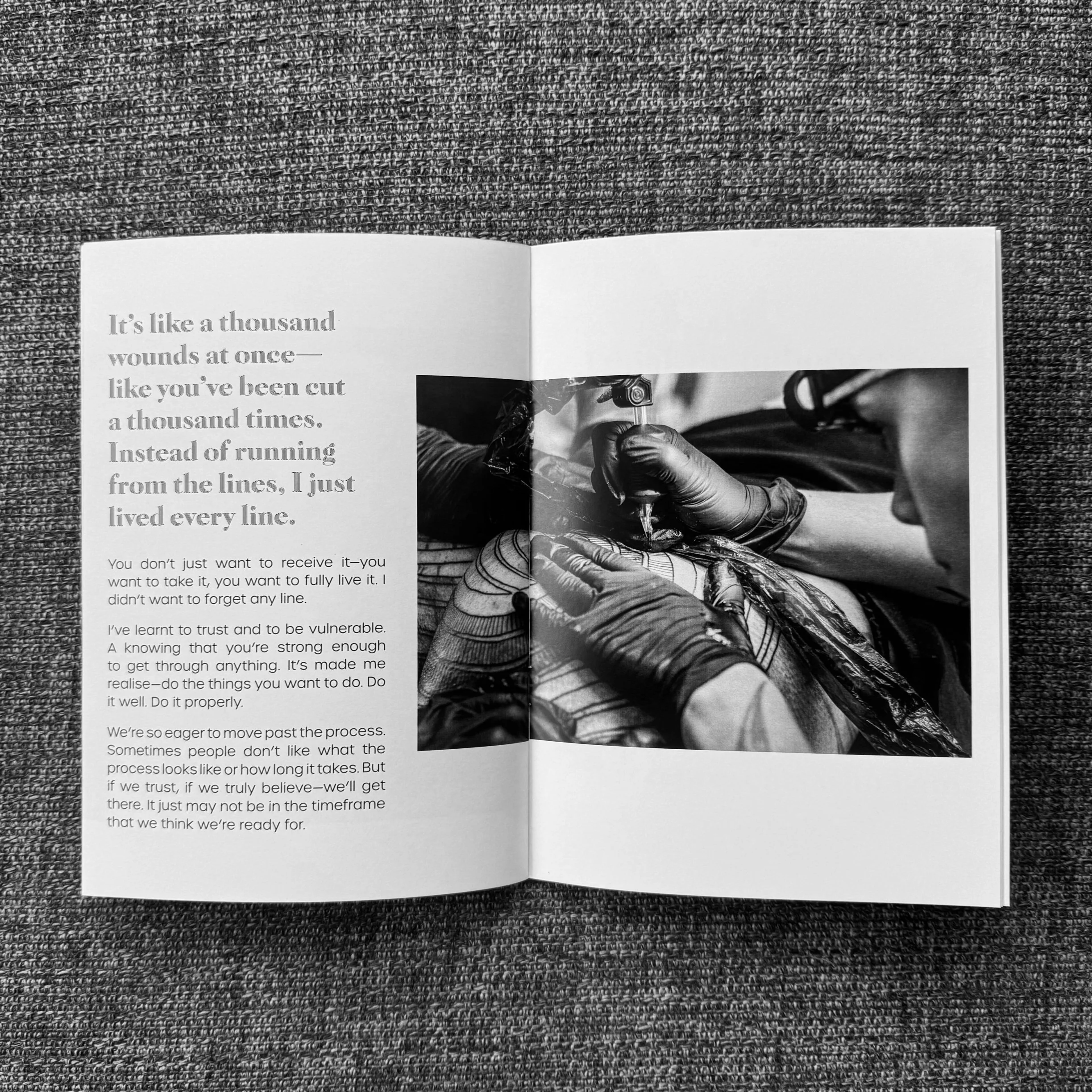

This was Fern’s first pūhoro wānanga, where she set up studio in the lounge of our whare. The wānanga ran over six consecutive days, with Jarrod and Fern tattooing for more than five hours each day. Pūhoro wānanga involve periods of drawing and long stretches of tā moko, broken up with breaks to refuel with kai and time to whakatau wairua—to settle and reset.

These wānanga are physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually demanding for both the kaiwhiwhi (receiver) and the kaitā (tā moko artist). Each has a role, working together with kaitautoko—stretchers and whānau supporters—to navigate pain, shifting energies and deep emotions.

There’s another layer when the person on the tēpū is your own whānau. Fern recalls tattooing Jarrod’s hope.

“The hope for anyone is always triggering. You go to a different place. The kōrero is, that’s where you store your trauma. When I was starting to tattoo Jarrod on his hope, I could feel his mamae and you can feel it in each line you do, you’re literally physically putting that person in pain, triggering someone that you love. I found it really difficult. I actually had to stop after we completed, I stopped and had a moment because I think that’s my first run in of being taken back by the experience.”

Fern describes pūhoro as a journey of going to Rarohenga and back—entering the spiritual realm of Uetonga, where the art of moko comes from. It’s not only physical, it’s ā-hinengaro, ā-wairua.

She says that shedding blood with your own people, in your own whare, is powerful. For her, creating taonga with and for our whānau felt like reclaiming our positions and power. That, to her, is what being urban Māori looks like—creating our own stories again, in our own spaces.

Reclaiming pūhoro in our whānau

Fern shares that in the times of our tīpuna, pūhoro were worn by warriors in combat. A warrior is someone who is agile, quickwitted, rooted in themselves and their community. Someone who is constantly working on themselves, constantly working with and for their people.

Pūhoro is still that now. But in our words, it represents leadership, service, responsibility and mana.

Today, reclaiming pūhoro has also become a journey of selfdevelopment. It’s a process of growing your mental and physical wellbeing to prepare—not just for the pūhoro wānanga, but for what pūhoro represents. For Fern and Jarrod, it’s about healing, identity, and figuring out who you are. Understanding your position and responsibilities in te ao Māori. Finding your place.

From Fern’s experience, that process often starts with doubt. ‘I don’t feel good enough, but I want it.’

“Every pūhoro that I’ve completed, they [kaiwhiwhi] play a pretty big role within their community and they know it, but they don’t even know it to the extent.”

That was true for Jarrod. Fern describes him as “very community driven… constantly working on himself, constantly working with his community… physically, he is someone who is in that warrior’s realm.”

When kaiwhiwhi want to undertake a pūhoro wānanga and are not sure if they’re ready, Fern asks, “What’s your role right now?” Because sometimes, being willing to go through this process—to sit for six days in pain—is itself a sign of the warrior within.

Receiving pūhoro in our whānau has become a way to reclaim who we are, how we show up, and the mana we carry—as ourselves, as urban Māori.

Story sovereignty

For Fern, opening up this wānanga and sharing her experience is part of the mahi.

“It’s not just that person getting stabbed a thousand times with a needle. It’s a whole different universe and realm that’s really going on. So for me to open up and share is, I think, yeah, mātauranga should always be shared when it should be—especially from a place of love and understanding and education.”

She sees her role now as not just creating moko, but creating spaces.

“Being able to be accessible for whānau and to guide them through that journey… that’s a big change. The more pūhoro that I do, it’s definitely a community.”

Sharing our story is part of our own reclamation. But it’s also about story sovereignty and mana motuhake. This is our story, in our voice, on our terms.

These interviews have been a way for us to reflect, to connect, to celebrate, and to heal. To sit with the emotions that rise, to process our journeys through storytelling as whānau. It’s intergenerational—a form of whakapapa in itself.

We’re sharing lived experiences that might not be widely heard or understood, in the hope that it supports others on their own reclamation journeys.

Reshaping narratives, perspectives, and mindsets is important to Fern and Jarrod. That’s the kaupapa of Urban Whakapapa—to hold space for intergenerational storytelling, to honour our own urban whakapapa, and to support otherson their reclamation journeys.

Nau mai te wānanga,

Deane-Rose Ngatai-Tua

Working with Āporo Press

Working with Damien Levi (Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi), who runs Āporo Press, made the process feel easy and grounded. Āporo Press is an independent Māori micro press — kaupapa-driven, and focused on uplifting bold, indigenous, and political voices. As soon as I read the call for submissions, I wanted to be part of it.

Damien was open, and supported me to take the lead. He was sensitive to tikanga — around te reo, image placement, and the way the story was held. That was important to me. It meant our kaupapa could land in a space where it would be understood, respected, and held with care.

This was my first time making a zine, and working with Damien made it feel natural. I will continure to explore this format.

Why Zines

Zines are a raw, unfiltered way of sharing stories — and for me, that connects to mana motuhake and story sovereignty.

I saw the zine format as a way to share our pūhoro wānanga with a wider audience — to hold space for lived experience, reflection, and reclamation, and to make our story something that could be picked up, held, and carried.

Zines feel accessible, while also creating taonga for our whānau and wider community. My hope is to create a series that shares personal stories and journeys as part of the wider wānanga of urban whakapapa — telling our stories in our own voice, on our own terms.

E mihi ana ki a koutou — Jarrod, Fern, and the team at Āporo Press for supporting this kaupapa

urban whakapapa: a thousand wounds on display at the Auckland Zinefest 2025