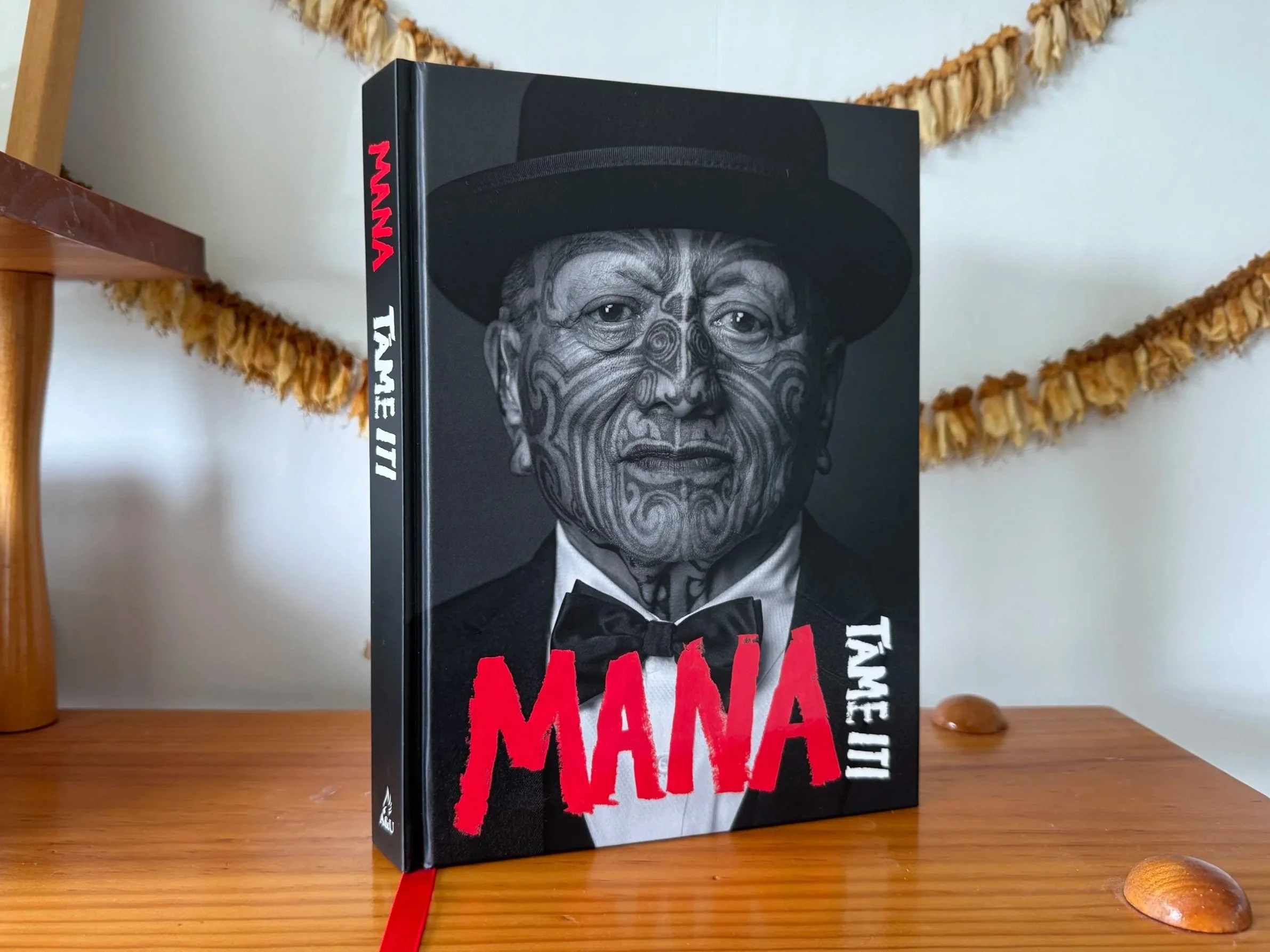

reading Mana by Tame Iti

Reflections from an urban Māori practitioner

I haven’t bought and read a book cover to cover in some time, but Mana was one I read from start to finish. It felt like the right book at the right time. Reading it now, in the current political climate in Aotearoa, and alongside recent tensions within Te Pāti Māori, felt timely. Tame Iti’s story is a reminder of activism, of standing for what is tika, and of the many ways that can be expressed — especially through art, storytelling, and lived experience.

From the start, the way Tame Iti reflects on his experiences feels like you’re sitting and listening to him share his story. It reminded me of the power of first-person storytelling, of using people’s own words to tell the story of their lived experiences. It was really easy to read.

The structure felt natural and easy to follow, like a journey. An evolving story of his life, his experiences, his growth, and the different phases he moved through. I liked how openly he talked about how he changed over time — how his mindset and worldview shifted as he learned more and experienced more.

The early chapters, where he talks about childhood, school, and later moving to Christchurch, stayed with me. Especially the way he reflects on what felt off or uneasy for him at the time — the experiences and questions he couldn’t yet articulate or fully understand. And then how, through reflection and experience, he became more aware of colonisation, racism, imperialism, capitalism. It reminded me of my own turning points and realisations — especially around colonisation, and when I learned that whakapapa for myself. When I started to see and experience institutional and overt racism, through tertiary education, and through my first governance experience on a school board. Working through my Masters thinking I was apolitical, and then coming out the other side realising I wasn’t. Being Māori is political.

Art and storytelling is a strong thread throughout Mana. Some quotes that stayed with me:

“Art was a conduit, a connection, giving voice to things that needed to be said.”

“That’s what I learnt about art: it’s capturing a moment, a thought, and preserving it in time.”

This made me reflect on my own journey — growing my practice and finding my voice again. That building a creative practice takes time, and that you actually have to make and create to find your style, and your voice.

One moment that really connected to urban whakapapa was his reflection on history and storytelling, as part of the Tūhoe Waitangi Tribunal claim where a research team interviewed claimants and recorded their stories. As Tame Iti writes:

“Elsdon Best became the accepted history of our iwi. But now instead of quoting from his pukapuka we could tell the authentic stories directly from the whānau and hapū that lived them.”

That sat with me. It speaks directly to why telling our own stories matters — especially urban Māori stories — and why urban whakapapa exists.

Mana also made me reflect on community development, Māori development, and systems change. Not only is Tame Iti an activist and artist — he is a community practitioner, supporting whānau and activating people. These quotes stayed with me:

“I still think there needs to be a war, but the war is internal. It is within our communities. It is within ourselves. It is a war against addiction, against dependence. It is a war against habits we have been conditioned to.”

“So change needs to come from grass roots.”

This really connected to my own journey. Working in government organisations, trying to change systems from the inside. And then starting my own business to work more at grassroots. Returning to my community in Rānui and working on the ground. That’s where I’ve felt most effective. That’s where I’ve felt my mana, and our mana, grow. Growing our own skills, our own confidence, our own ability to create change — rather than waiting for systems to shift.

Mana also made me think about art as performance. About self-expression and theatre. About how the acts we do every day can make a statement. The ways in which Tame Iti delivers kaupapa at hui and wānanga is strategic, intentional, and performative — designed to captivate, to move people. This reframes how I think about leadership, facilitation, and storytelling in my own mahi.

It made me reflect on how I show up. What does taking a stand look like for me now, in this phase of my life and practice? What does it mean to be visible, to be brave, while staying grounded in community, creativity, and care?

These are questions I’m still sitting with. Bringing me back to mana — what it means in practice, and the responsibility carried through whakapapa and action.